Managing Partner at Dragonfly. Effective Altruist. Airbnb, Earn.com (acquired by Coinbase) alum. Writer. Former poker pro. Donate 33% of my income to charity.

more

A useful currency should be a medium of exchange, a unit of account, and a store of value. Cryptocurrencies excel at the first, but as a store of value or unit of account, they’re pretty bad. You cannot be an effective store of value if your price fluctuates by 20% on a normal day.

This is where stablecoins come in. Stablecoins are price-stable cryptocurrencies, meaning the market price of a stablecoin is pegged to another stable asset, like the US dollar.

It might not be obvious why we’d want this.

Bitcoin and Ether are the two dominant cryptocurrencies, but their prices are volatile. A cryptocurrency’s volatility may fuel speculation, but in the long run, it hinders real-world adoption.

Businesses and consumers don’t want to be exposed to unnecessary currency risk when transacting in cryptocurrencies. You can’t pay someone a salary in Bitcoin if the purchasing power of their wages keeps fluctuating. Cryptocurrency volatility also precludes blockchain-based loans, derivatives, prediction markets, and other longer-term smart contracts that require price stability.

And of course, there’s the long tail of users who don’t want to speculate. They just want a store of value on a censorship-resistant ledger, escaping the local banking system, currency controls, or a collapsing economy. Right now, Bitcoin and Ethereum can’t offer them that.

The idea of a price-stable cryptocurrency has been in the air for a long time. Much cryptocurrency innovation and adoption has been bottlenecked around price-stability. For this reason, building a “stablecoin” has long been considered the Holy Grail of the cryptocurrency ecosystem.

But how does one design a stablecoin? To answer that question, we first have to deeply understand what it means for an asset to be price-stable.

All stablecoins imply a peg. Stablecoins generally peg to the US dollar (so each stablecoin trades at $1), but they sometimes peg to other major currencies or to the consumer price index.

Of course, you can’t just decide an asset should be valued at a certain price. To paraphrase Preston Byrne: a stablecoin claims to be an asset that prices itself, rather than an asset that is priced by supply and demand.

This goes against everything we know about how markets work.

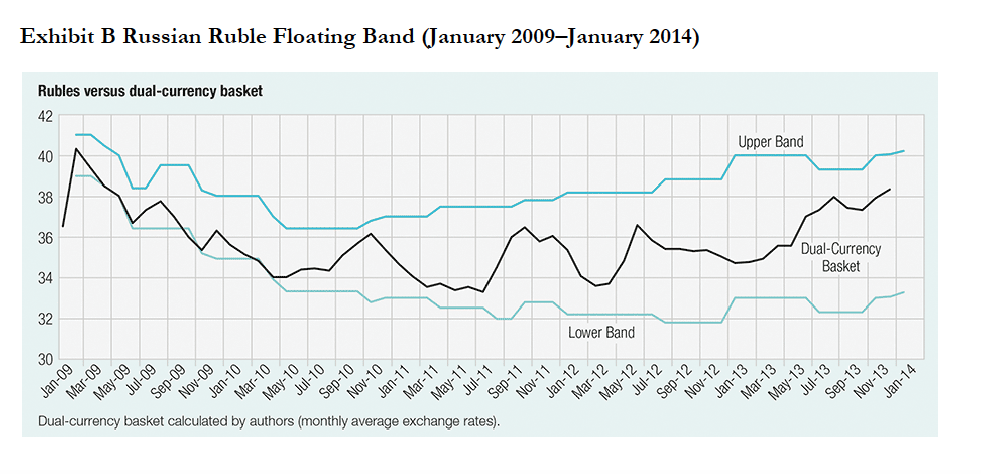

This is not to say that stablecoins are impossible. Stablecoins are just currency pegs, and currency pegs are certainly not impossible—there are many currency pegs still being maintained. However, almost all large central banks have moved away from currency pegs. This is in part because they’ve realized pegs tend to be inflexible and difficult to maintain. History has taught us again and again, whether it be Mexican peso crisis of 1994, the Ruble crisis of 1998, or the infamous Black Wednesday (when George Soros “broke the bank of England”), no currency peg can be maintained against sufficiently adverse conditions.

But this is an incomplete analysis.

The reality is, any peg can be maintained, but only within a certain band of market behavior. For different pegs the band might be wider than others. But it’s straightforwardly true that within at least some market conditions, it’s possible to maintain a peg. The question for each pegging mechanism is: how wide is the band of behavior it can support?

If you assume currency markets are performing a random walk, this implies every peg will eventually walk outside of its stable band and break. But the sun will also eventually swallow up the solar system, so screw it—we can call a peg stable if it lasts 20 years. Even in fiat years, that’s pretty good.

The question for any peg then is four-fold:

The final two points matter a great deal, because currency pegs are all about Schelling points. If market participants cannot identify when a peg is objectively weak, it becomes easy to spread false news or incite a market panic, which can trigger further selling—basically, a death spiral. A transparent peg is more robust to manipulation or sentiment swings.

To summarize, an ideal stablecoin should be able to withstand a great deal of market volatility, should not be extremely costly to maintain, should have easy to analyze stability parameters, and should be transparent to traders and arbitrageurs. These features maximize its real-world stability.

These are the dimensions along which I’ll analyze different stablecoin schemes.

So how can you design a stablecoin?

The more stablecoin schemes I’ve examined, the more I’ve realized how small the space of possible designs actually is. Most schemes are slight variations of one another, and there are only a few fundamental models that actually work.

At a high level, the taxonomy of stablecoins includes three families: fiat-collateralized coins, crypto-collateralized coins, and non-collateralized coins. We’ll analyze each in turn.

If you want to build a stablecoin, it’s best to start with the obvious. Just create a cryptocurrency that’s literally an IOU, redeemable for $1.

You deposit dollars into a bank account and issue stablecoins 1:1 against those dollars. When a user wants to liquidate their stablecoins back into USD, you destroy their stablecoins and wire them the USD. This asset should definitely trade at $1—it is less a peg than just a digital representation of a dollar.

This is the simplest scheme for a stablecoin. It requires centralization in that you have to trust the custodian, so the custodian must be trustworthy. You’ll also want auditors to periodically audit the custodian, which can be expensive.

But with that centralization comes the greatest price-robustness. This scheme can withstand any cryptocurrency volatility, because all of the collateral is held in fiat reserves and will remain intact in the event of a crypto collapse. This cannot be said for any other type of stablecoin.

A fiat-backed scheme is also highly regulated and constrained by legacy payment rails. If you want to exit the stablecoin and get your fiat back out, you’ll need to wire money or mail checks—a slow and expensive process.

Pros:

Cons:

This is essentially what Tether purports to be, though they have not been recently audited and many people suspect Tether is actually a fractional reserve and don’t hold all of the fiat as they claim they do. Other stablecoins like TrueUSD are trying to do the same thing, but with more transparency. Digix Gold is a similar scheme, except the collateral is gold instead of fiat. Nevertheless, it shares the same fundamental properties.

Say we don’t want to integrate with the traditional payment rails. After all, this is crypto-land! We just reinvented money, why go back to centralized banks and state-backed currencies?

If we move away from fiat, we can also remove the centralization from the stablecoin. The idea falls out naturally: let’s do the same thing, but instead of USD, let’s back the coin with reserves of another cryptocurrency. That way everything can be on the blockchain. No fiat required.

But wait. Cryptocurrencies are unstable, which means your collateral will fluctuate. But a stablecoin obviously shouldn’t fluctuate in value. There’s only one way to resolve this catch-22: over-collateralize the stablecoin so it can absorb price fluctuations in the collateral.

Say we deposit $200 worth of Ether and then issue 100 $1 stablecoins against it. The stablecoins are now 200% collateralized. This means the price of Ether can drop by 25%, and our stablecoins will still be safely collateralized by $150 of Ether, and can still be valued at $1 each. We can liquidate them now if we choose, giving $100 in Ether to the owner of the stablecoins, and the remaining $50 in Ether back to the original depositor.

But why would anyone want to lock up $200 of Ether to create some stablecoins? There are two incentives you can use here: first, you could pay the issuer interest, which some schemes do. Alternatively, the issuer could choose to create the extra stablecoins as a form of leverage. This is a little subtle, but here’s how it works: if a depositor locks up $200 of Ether, they can create $100 of stablecoins. If they use the 100 stablecoins to buy another $100 of Ether, they now have a leveraged position of $300 Ether, backed by $200 in collateral. If Ether goes up 2x, they now have $600, instead of the $400 they’d otherwise make.

Fundamentally, all crypto-collateralized stablecoins use some variant of this scheme. You over-collateralize the coin using another cryptocurrency, and if the price drops enough, the stablecoins get liquidated. All of this can be managed by the blockchain in a decentralized way.

We neglected one critical detail though: the stablecoin has to know the current USD/ETH price. But blockchains are unable to access any data from the external world. So how you can you know the current price?

The first way is to simply have someone continually publish a price feed onto the blockchain. This is obviously vulnerable to manipulation, but this may be good enough if the publisher is trustworthy. The second way is to use a Schelling Coin scheme, along the lines of TruthCoin. This is much more complex and requires a lot of coordination, but is ultimately less centralized and less manipulable.

Crypto-collateralized coins are a cool idea, but they have several major disadvantages. Crypto-collateralized coins are more vulnerable to price instability than fiat-collateralized coins. They also have the very unintuitive property that they can be spontaneously destroyed.

If you collateralize your coin with Ether and Ether crashes hard enough, then your stablecoin will automatically get liquidated into Ether. At that point you’ll be exposed to normal currency risk, and Ether may continue to fall. This could be a dealbreaker for exchanges—in the case of a market crash, they would have to deal with stablecoin balances and trading pairs suddenly mutating into the underlying crypto assets.

The only way to prevent this is to over-collateralize to the hilt, which makes crypto-collateralized coins much more capital-intensive than their fiat counterparts. A fiat-backed cryptocurrency will require only 100K collateral to issue 100K stablecoins, whereas a crypto-collateralized coin might require 200K collateral or more to issue the same number of coins.

Pros:

Cons:

The first stablecoin to use this scheme was BitUSD (collateralized with BitShares), created by Dan Larimer back in 2013. Since then, MakerDAO’s Dai is widely considered the most promising crypto-collateralized stablecoin, collateralized by Ether. An interesting scheme proposed by Vitalik Buterin is using CDOs to issue stablecoins against loans with different tranches of seniority (the most senior tranches could act as stablecoins).

As you get deeper into crypto-land, eventually you have to ask the question: how sure are we that we actually need collateral to begin with? After all, isn’t a stablecoin just a coordination game? Arbitrageurs just have to believe that our coin will eventually trade at $1. The United States was able to move off the gold standard and is no longer backed by any underlying asset. Perhaps this means collateral is unnecessary, and a stablecoin could adopt the same model.

This idea is not completely novel—its roots can be traced to arguments made by F.A. Hayek in the 70s. A privately issued, non-collateralized, price-stable currency could pose a radical challenge to the dominance of fiat currencies. But how would you ensure it remains stable?

Enter Seignorage Shares, a scheme invented by Robert Sams in 2014. Seignorage Shares is based on a simple idea. What if you model a smart contract as a central bank? The smart contract’s monetary policy would have only one mandate: issue a currency that will trade at $1.

Okay, but how could you ensure the currency’s trading price? Simple—you’re issuing the currency, so you get to control the monetary supply.

For example, let’s say the coin is trading at $2. This means the price is too high—or put another way, the supply is too low. To counteract this, the smart contract can mint new coins and then auction them on the open market, increasing supply until the price returns to $1. This would leave the smart contract with some extra profits. Historically, when governments minted new money to finance their operations, the profits were called the seignorage.

But what if the coin is trading too low? Let’s say it’s trading at $0.50. You can’t un-issue circulating money, so how can you decrease the supply? There’s only one way to do it: buy up coins on the market to reduce the circulating supply. But what if the seignorage you’ve saved up is insufficient to buy up enough coins?

Seignorage Shares says: okay, instead of giving out my seignorage, I’m going to issue shares that entitle you to future seignorage. The next time I issue new coins and earn seignorage, shareholders will be entitled to a share of those future profits!

In other words, even if the smart contract doesn’t have the cash to pay me now, because I expect the demand for the stablecoin to grow over time, eventually it will earn more seignorage and be able to pay out all of its shareholders. This allows the supply to decrease, and the coin to re-stabilize to $1.

This is the core idea behind Seignorage Shares, and some version of this undergirds most non-collateralized stablecoins.

If you think Seignorage Shares sounds too crazy to work, you’re not alone. Many have criticized this system for an obvious reason: it resembles a pyramid scheme. Low coin prices are buttressed by issuing promises of future growth. That growth must be subsidized by new entrants buying into the scheme. Fundamentally, you could say that the “collateral” backing Seignorage Shares is shares in the future growth of the system.

Clearly this means that in the limit, if the system doesn’t eventually continue growing, it will not be able to maintain its peg.

Perhaps that’s not an unreasonable assumption though. After all, the monetary base for most world currencies have experienced nearly monotonic growth for the last several decades. It’s possible that a stable cryptocurrency might experience similar growth.

But there’s no free lunch in economics. Seignorage Shares can absorb some amount of downward pressure for a time, but if the selling pressure is sustained for long enough, traders will lose confidence that shares will eventually pay out. This will further push down the price and trigger a death spiral.

The most dangerous part of this system is that it’s difficult to analyze. How much downward pressure can the system take? How long can it withstand that pressure? Will whales or insiders prop up the system if it starts slipping? At what point should we expect them intervene? When is the point of no return when the system breaks? It’s hard to know, and market participants are unlikely to converge. This makes the system is susceptible to panics and sentiment-based swings.

Non-collateralized stablecoins are also vulnerable to a secular decline in demand for crypto, since such a decline would inevitably inhibit growth. And in the event of a crypto crash, traders tend to exit to fiat currencies, not stablecoins.

These systems also need significant bootstrapping of liquidity early on until they can achieve healthy equilibrium. But ultimately, these schemes capitalize on a key insight: a stablecoin is, in the end, a Schelling point. If enough people believe that the system will survive, that belief can lead to a virtuous cycle that ensures its survival.

With all that said, non-collateralized stablecoins are the most ambitious design. A non-collateralized coin is independent from all other currencies. Even if the US Dollar and Ether collapse, a non-collateralized coin could survive them as a stable store of value. Unlike the central banks of nation states, a non-collateralized stablecoin would not have perverse incentives to inflate or deflate the currency. Its algorithm would only have one global mandate: stability.

This is an exciting possibility, and if it succeeds, a non-collateralized stablecoin could radically change the world. But if it fails, that failure could be even more catastrophic, as there would be no collateral to liquidate the coin back into and the coin would almost certainly crash to zero.

Pros:

Cons:

The most promising project in this category is Basecoin, which builds upon Seignorage Shares by adding a first-in-first-out “bond” queue. They claim that this addition improves the stability properties of the protocol, and have performed several simulations to model various outcomes.

Stablecoins are critical to the future of crypto. The differences between these designs are subtle, yet matter immensely.

But after having looked at many of these, my primary conclusion is that there is no ideal stablecoin. Like with most technologies, the best we can do is choose the set of tradeoffs that we’re willing to accept for a given application and risk profile.

The best outcome then, is not to try to pick winners early, but rather to encourage the many stablecoin experiments to bear their fruit in the marketplace.

If crypto has taught us anything, it’s that it’s very hard to predict the future. I suspect there are many more variations on these schemes waiting to be unearthed. But whichever stablecoins win in the long run, they’ll almost certainly build on one of these fundamental designs.

How do you govern a blockchain? That might sound like a strange question. In theory, blockchains aren’t supposed to be governed at all—they’re supposed to be “permissionless decentralized ledgers.” But a blockchain is more than just a ledger. It’s also an ecosystem of software, an economy of merchants, companies, and exchanges, and beneath all that, a community of developers, miners, and users. At the end of the day, blockchains must...

read more

Cryptocurrencies, ICOs, magic internet money—it’s all so damn exciting, and you, the eager developer, want to get in on the madness. Where do you start? I’m glad you’re excited about this space. I am too. But you’ll probably find it’s unclear where to begin. Blockchain is moving at breakneck speed, but there’s no clear onramp to learning this stuff. Since I left Airbnb to work full-time on blockchain, many people...

read more